Written by Roxanne Fequiere

When a parent repeats herself, a daughter must listen.

• • •

My mother sighs like no one I’ve ever met. The five siblings she helped raise, the country she left behind, the four decades of marriage, the patients she cared for, the three children she bore and the one she did not. The limitless sacrifice, the scant reciprocity, it’s all there, stage-whispered to anyone within earshot in every layered, labored exhalation. She can wield these sighs like weapons, and often does, deploying them at will to evoke guilt, shame, fear, or to simply bring an uncomfortable conversation to an immediate end.

As the youngest of my mother’s three children and her only daughter, I can hear subtle nuances in her sighs that the untrained ear cannot. I learned long ago how to differentiate between a sigh of mere exasperation and one that signaled a deep depression, or whether an outburst or a droning lecture was looming.

This skill was less the result of natural instinct than my mother’s tendency to share her emotions in fits and starts. Despite her desire to keep certain portions of her history and interior life under wraps, she made a habit of lobbing stray memories and anecdotes at me, each a footnote from a tragic memoir, the words falling from her lips like a favorite passage in a well-worn book. There were the tales of living under a dictatorship back in Haiti, a reluctance to express even low-level discontent regarding the government on the off chance you were speaking to an informant, the fear of being snatched away in the dead of night by the Tonton Makout, your dead body turning up days later as a warning to your family and friends.

There were several stories about beatings, her parents’ preferred method of discipline. One of her brothers was especially hardheaded, never turning down an opportunity to question authority. Some of the thrashings he endured were so severe she feared he might not survive them. An obedient child herself, she rarely experienced beatings, but watching them happen convinced her early on that she would never hit her own children. “When I was growing up, if my parents said something, you listened. Period. Or else,” she’d say. “I always promised myself that when I had my own kids, I would sit them down and explain the reasoning behind my rules.”

After years of being told these stories over and over, I was dumbfounded when my aunt shared a funny anecdote about her and some of her siblings pranking a disliked houseguest when they were kids. To hear my mother describe her childhood, in that era, in that country, was to imagine pure doom and gloom. It hadn’t dawned on me that there had also been joy, and laughter.

Even my mother’s happier stories contained sorrowful notes. A recollection of, say, a particularly striking outfit from her youth would end with a downtrodden outro: “Now I’ve given birth to three kids, I spend all my money on you guys, and I look like this.”

Some stories she felt comfortable sharing in mixed company, with my brothers or my father within earshot. Others were meant for my ears only. Like how she’d been advised not to try for another pregnancy after my two brothers were born, but desperate to have a girl she’d defied orders and succeeded. Her expectations of me were boundless and quite clear from the beginning—I was to reach unscalable heights of excellence and step in to complete the mother-daughter bond that she had always longed for with her own mother. I was doomed from the start.

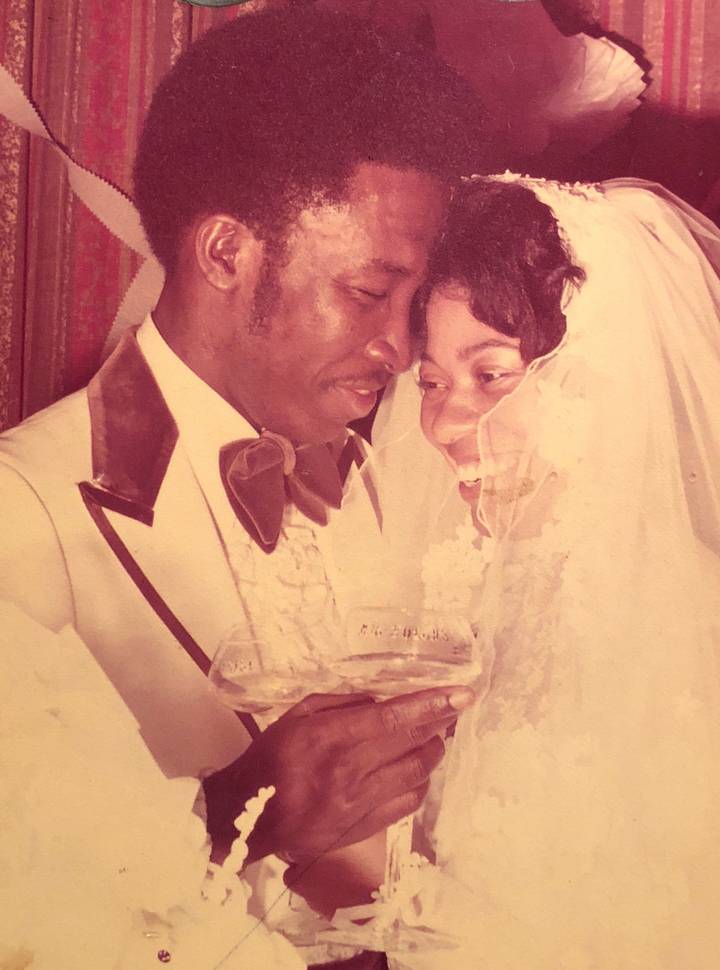

MarieYolens Fequiere in or around 1984, before the author was born.

When my grandmother died, five months after my grandfather on a cloudy day in July, my 16th birthday, I remember my mother saying quietly to no one in particular, “I’m an orphan now.” It’s a sentiment that’s resurfaced on the 13 birthdays since, whether in person or over the phone, directly after a string of well wishes and expressions of pride. “I never thought I’d be an orphan,” she says every year. “I used to get down on my knees every night and beg God to keep my parents alive for as long as possible….” I’ve never been able to tell her that I think He did. I’ve never known how to buoy her once she descends into that space, to get her back on the subject of candles and balloons.

The death of my grandparents triggered another tradition, another recitation that my mother initiates at midnight every New Year’s Eve, the official start of her own birthday. “This is the first year that I’m not getting a call from my parents,” she said on New Year’s Day in 2005, her voice wobbling, nose red from repeated contact with the tissue in her hand. “I still feel like I’m waiting for my parents to call,” she said the second year, and every year since. She describes what was said during each call—well-wishes, expressions of pride—and how she loved that their voices began each year for her. I apologize every year for reasons I’m not quite sure of. Perhaps because even though I make sure my voice is now the first she hears each year, it isn’t enough to fill the void. Perhaps because I know how difficult it can be for a day of joy and fresh starts to be forever tied to a painful memory.

“Even my mother’s happier stories contained sorrowful notes.”

A rear-end collision removed my mother from the workforce several years ago, the impact throwing into high relief the compounded strain she’d acquired over a decade of lifting developmentally disabled patients into and out of their daily baths. Two back surgeries have done little to improve her mobility.

A few years after that, my brother became the last of us to move out of the house, a perceived slight she took personally. “Your brother is moving to North Carolina. I don’t know what I did to make him do this,” she told me over the phone.

“Mom, he’s 31,” I said. “He just wants to be on his own. I don’t think it has anything to do with you.”

“I don’t know what I did to make him do this,” she repeated. She’s always regarded our independence as a kind of betrayal.

On my birthday last year, I was pleased to get a call from her, wishing me well. Two days later, she called, apologizing profusely and, again, wishing me well—did she miss my birthday? When I came home to visit with my partner of 11 years, she dutifully asked after his younger brother, if he’s graduated yet, what he’s up to. She shuffles off to check on dinner, returns, and repeats her question, seemingly unaware that it’s already been answered.

These days, the redemptive anecdotes come few and far between. Gone are the stories of turning heads on her way to work at the National Reserve Bank, not a hair out of place, or of meeting my father on a New York City street corner, him racing toward her and asking for a dime in order to call his mother to tell her he’d met the woman he was going to marry. What’s left are memories of despair, rejection, and failure.

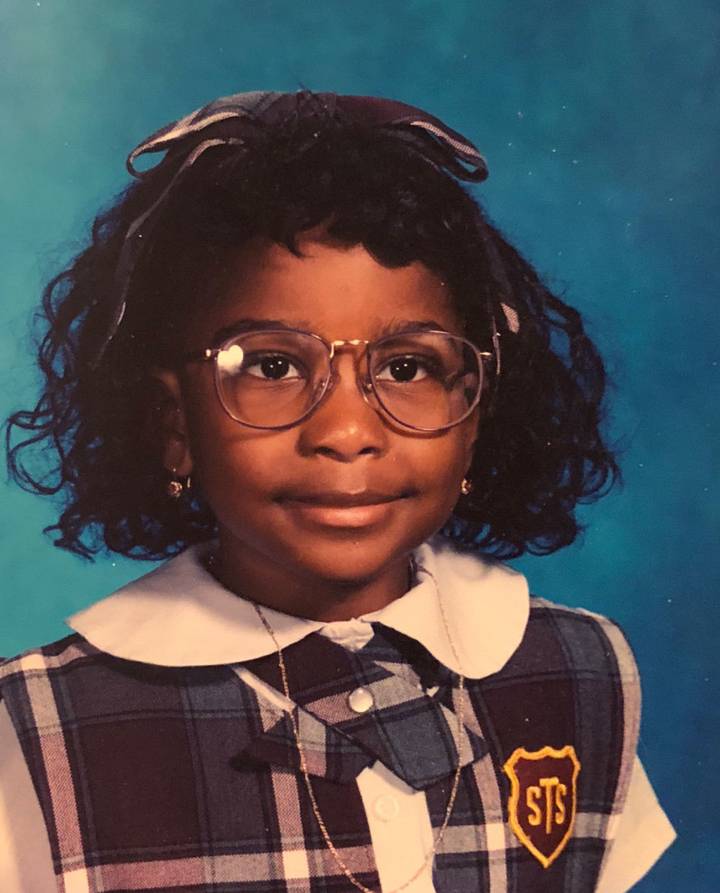

Pictured: the author in 1995

“She’s always regarded our independence as a kind of betrayal.”

When my mother turned 65, we went out to dinner and I asked her what was next. Diana Nyad had made headlines that summer for her historic swim from Cuba to Florida at the age of 64. To reporters waiting on the beach for her, she said, “You are never too old to chase your dreams.” I repeated as much to my mom, telling her that this birthday could signal a new beginning. “Speaking of swimming,” she said, “learning to do that would be nice—”

“Let’s do it!” I said. “I’ll find an adult class and go with you.”

“—but I don’t think I’d feel comfortable in a swimsuit.”

“If I found private lessons for you, would you do it?”

I took her half-shrug as a yes. “Done. What else?”

We talked about going to Europe—I would be responsible for creating an itinerary that allowed her to see the sights despite her limited mobility. But when I planned a three-month trip the following year and asked her to accompany me on a leg of it, she rebuffed my invitation so viciously it made me cry. She began ducking out of family get-togethers for no particular reason. She seemed to be shrinking into herself somehow, vehemently demanding that she be left alone to do so.

When I wasn’t trying to convince her to expand her horizons—to get a passport or join a book club—I was asking when she planned on seeing a doctor about her memory problems. She’d started calling multiple times a day to ask the same simple question I’d already answered. If I asked about a specific bill or piece of mail, she might get worked up to the point of tears, unable to remember where she’d placed it. At times when she did venture outside, the tone of her calls turned frantic. She’s somewhere in the Bronx, lost, crying in frustration. The GPS has led her astray, and now that the sun has gone down, she can no longer read the signs on the highway.

After one of these incidents, I accompanied her home, my father in the driver’s seat, my mother riding shotgun, and me in the backseat, with my partner trailing behind, driving my mother’s car home for her. We needed to talk, I told her, all of us.

She’d been living in denial, and my brothers and I had been trying to figure out how to get her to see a doctor or find a caregiver, something. “I don’t want to have a family discussion,” she said, with a sharpness I remembered from our Europe arguments. “But if you want to talk, you’re free to spend the night.”

“Why would I spend the night?” I asked. “I’m right here, asking to talk to you now.” And then I realized she was telling me, in her way, that she had something to say that was meant for my ears only.

When we were alone, I told her how much I loved her, how much I wanted her to take care of her health, to thrive. She nodded, said she understood, thanked me for my concern, paused for a beat, and began to speak—about the five siblings she helped raise, the country she left behind, the four decades of marriage, the three children she bore and the one she did not, the limitless sacrifice, the scant reciprocity.…

It was a script I knew well. As a child, it was recited so often that it took on the familiarity of a dark fairy-tale series—heavy on lessons learned, light on happy endings. The way I understood it then: My mother’s selflessness and obedience had backed her into a dutiful corner for much of her life, and if I were to avoid a similar fate, I had to live on my own terms. Years later, when I tried to do just that and was rebuffed at every turn, I wondered if perhaps my brothers and I were supposed to have been her happy ending. Each story seemed equipped with hooks, poised to drag me back home, and I did my best to dodge her frequent recitals—all the better to avoid the inevitable guilt trip. I feel no such angst anymore when I hear those opening strains of my mother’s oft-repeated narrative. They still pain me, but my childhood conclusions were correct. I can only do my best to avoid the pitfalls she stumbled into.

“Mom. Mom,” I pleaded. “We’ve been through this already. I know. And I’m sorry. But I want to talk about how we can improve your life going forward.”

“This is what I want to talk about,” she shouted back. And so it went.

Growing up, there were quiet moments in which I could hear my mother’s sigh from another room and, upon closer inspection, deduced that it was a private admission; she was the storyteller and audience. She always knew just how to maneuver those sounds, and I’m finally learning how to deflect their effects. I wonder if she should have done the same, if she could have found a way to share her sadness without letting it sink so deeply, so irreversibly into her skin. My mother made a habit of using her darkest memories like a weapon to extract pity from anyone who would listen, but now I know the blade always cut both ways.

ROXANNE FEQUIERE is a New York–based writer and editor who might just make it after all.